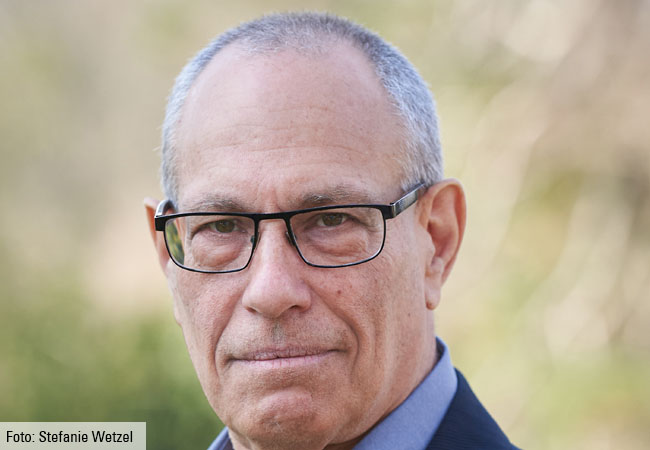

Nimrod Hurvitz is a visiting researcher at Goethe University’s Forschungskolleg Humanwissenschaften – Institute of Advanced Studies, focusing on the topic of “Targeting Archaeology: Emotions and Agendas Behind IS’s Heritage Destruction”.

UniReport: Professor Hurvitz, why were archaeologists so confused by the destruction committed by the Islamic State? What made this destruction so special, given that humiliating the enemy has always been part of military strategy?

Nimrod Hurvitz: Between 2014 and 2016, the terrorist organization IS (Islamic State), which had taken control of territories across the Middle East, systematically destroyed significant portions of the religious and cultural heritage in Syria and Iraq. Targets included archaeological sites, museum artifacts, mosques, churches, shrines, and cemeteries. When news of this cultural devastation reached archaeologists, international organization staff, and cultural heritage advocates, it sparked outrage. However, some archaeologists criticized the way this destruction was condemned and the focus on damage assessments, arguing that such attention only encouraged IS to intensify their campaign of destruction.

After the wave of destruction subsided, scholars began investigating why IS invested its scarce resources into the destruction of cultural property. Researchers identified several valid reasons: IS sought to attract radical Muslim followers, humiliate Western powers and regional authorities, and demoralize local populations. Most observers and analysts conclude that IS considers the destruction of cultural heritage part of a calculated strategy designed to shock its enemies and throw them off balance.

How would you describe your approach to understanding the motivation(s) behind IS’s actions? What is your methodology, and what sources do you use?

The research project “Targeting Archaeology: Emotions and Agendas Behind IS’s Heritage Destruction”, which I am conducting during my stay at the Forschungskolleg Humanwissenschaften in collaboration with Professor Hagit Nol’s project “Islamic Archaeology and Art History”, examines the destruction campaign through a new lens – that of the history of emotions. This approach assumes that collective emotions – such as patriotism, feelings of group superiority, racism, moral panic, or the fear of epidemics – play a crucial role in social and political dynamics. Applying this historiographical method allows us to deepen our scholarly understanding of IS as a movement driven by emotion. It explores how emotions contributed to the rise of the Islamic State, shaped its policies (especially at the peak of its power and during the establishment of the caliphate), and influenced how it dealt with failure, i.e. the fall of the caliphate. This emotional perspective adds critical insights to existing strategic and ideological analyses of the group’s destruction campaign.

The project specifically investigates how the destruction campaign affected the perpetrators themselves. Rather than analyzing how these acts of cultural annihilation impacted victims — such as local populations, militias, national armies, or global powers — this study examines in how far participating in this destruction stemmed from and shaped the emotions of IS members: Did staging these acts of destruction empower them? How did iconoclastic acts strengthen group cohesion? To what extent did destroying cultural property give members a heightened sense of purpose and historical significance? By focusing on the emotional dynamics of the destruction instead of its external effects, this study offers a new perspective on IS.

To answer these questions, the study first examines the targeted sites and artifacts. It then explores how IS discussed and used these acts, following on by framing the destruction within IS’s ideology and emotional manipulation. It’s important to note that in IS’s worldview, emotion and ideology are deeply intertwined – as illustrated, for example, by the principle of “al-walāʾ wa-l-barāʾ” (“loyalty and disavowal”), which demands total devotion to fellow believers and active hatred toward outsiders. This emotional dichotomy is reinforced with historical examples, like when IS members are encouraged to emulate Abraham, who, according to monotheistic tradition, destroyed his family’s idols to reject polytheism. This provides the theological justification for contemporary acts of cultural destruction.

If we better understand IS’s motivations, could that help us develop strategies to protect cultural heritage more effectively? Or is that merely wishful thinking?

Studying cultural destruction reveals several deep layers of IS’s worldview and helps us better understand a movement that played a central role in Middle Eastern civil wars and inflicted trauma on the region’s people. Beyond the local impact, IS’s violence triggered waves of migration to Europe and as a result has since shaped European politics. By investigating its targeted attacks on religious and cultural landscapes, we can uncover the emotional and ideological foundations of a movement whose influence extends far beyond the Middle East.

Some might wonder whether such an understanding can lead to policies that reduce IS’s destructive power and mitigate the damage it caused. Honestly speaking – I doubt it. However, research can help inform political strategies aimed at weakening IS – particularly in how we deal with individuals who are complicit but not fully committed to the group or its ideology.

How have you found your time at Forschungskolleg Humanwissenschaften and the exchange with other researchers so far?

Forschungskolleg Humanwissenschaften offers an excellent environment for research. The staff’s professionalism and warmth make the stay both smooth and enjoyable. The discussions with other fellows – many of whom are researching different political crises of our time – are often insightful and always collegial. I can’t imagine a more supportive research environment.

Nimrod Hurvitz teaches at the Department of Middle East Studies at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. He is in Frankfurt at the invitation of Hagit Nol, Junior Professor of Islamic Archaeology at Goethe University Frankfurt. His stay is supported by the Volkswagen Foundation-funded project “Islamic Archaeology and Art History” (IAAH).